| |

|

|

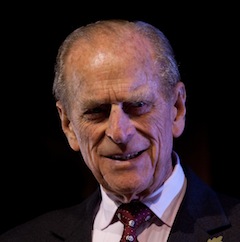

Interview with Prince Philip

|

|

|

Prince Philip hosting a key ARC event at Windsor Castle in 2009 |

HRH The Prince Philip was the inspiration behind the original WWF network of religions and conservation in 1986. In 1995 he founded the Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC) and he has continued to support the charity ever since. ARC writer Victoria Finlay interviewed him, to find out how it all began.

How did you first become involved with the conservation movement?Most people with any knowledge of the countryside have been concerned about the degradation of the natural environment and decline of wild species for quite a long time. I got to know Peter Scott and Aubrey Buxton many years ago and this led to my becoming President of Peter Scott's Wildfowl Trust. This then led me to being invited to become President of WWF-UK when it was founded and a Trustee of WWF-International. I was invited to become President of WWF-International in 1981.

Can you talk about the origins of ARC? WWF was founded in 1961, so 1986 was its 25th anniversary. There was much discussion about where to have the anniversary international conference, and in the end Assisi was chosen, for fairly obvious reasons. [Assisi was the home of St Francis, patron saint of wild animals] The plan was for the "secular" conference to take place in the town, but I thought that it would be a good idea to take advantage of Assisi to try to get the major religions to take an interest in the conservation of nature.

What first gave you the idea of bringing conservationists and religious leaders together? In the 1980s WWF International was trying to do three things around the world: raise money, develop conservation projects and educate the public. The first two things were fine, but the last one had real difficulties. I argued that the kind of education we were doing through articles and lectures and books and films and things of that sort only reached the educated and probably only the middle classes in the various countries.

The people that we needed to get to were the ones who lived in the areas of greatest risk, and the areas where the potential for biological diversity was highest. It occurred to me that the people who could most easily communicate with them were their religious leaders. They are in touch with their local population more than anyone else. And if we could get the local leaders to appreciate their responsibility for the environment then they would be able to explain that responsibility to the people of their faith.

It didn't seem a particularly bright idea at the time - it was pretty obvious. If your religion tells you (as it does in Christianity anyway) that the Creation of the world was an act of God, then it follows naturally that if you belong to the church of God then you ought to look after His Creation. It may not be sacred itself but the One who created it is sacred - so it seems logical that humans ought to have a certain responsibility for it.

|

HRH Prince Philip has attributed his interest in conservation to a medium-format camera. It was a Hasselblad, and he bought it in Stockholm during the 1956 Equestrian Olympics. However he only really began to use it on the long voyage home from the Melbourne Summer Olympics –to take pictures of the birds he saw from the Royal Yacht Britannia as he returned via the South Atlantic. Bird-watching led naturally to meeting bird-conservationists, and “almost before I could tell the difference between a Bewick and a Whooper, Peter Scott got me involved in the formation of the World Wildlife Fund.”

P7 The Environmental Revolution, HRH The Prince Philip, New York: The Overlook Press, 1978 |

|

|

|

I was not quite sure what the other religions believed about the creation of the world but I guessed that they had similar traditions. I therefore suggested that WWF should invite leaders from the major religions to meet together to discuss what - if any - responsibility they felt they had for the natural environment as a "sacred" entity.

What happened at Assisi? The five religious leaders [representing Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism] agreed that they had a responsibility and then we asked each of them to describe the attitude of their religion to the natural environment. We said: "we don't want to be ecumenical; we don't want a paper that has been agreed by everybody. Instead we want each of you to say what is relevant to you and your tradition".

That avoided any business of trying to achieve any ecumenical solution. But it also gave them the opportunity to talk to each other because there was no talk about dogma or if there was, then it was just about saying "well this is our dogma and this is yours".

The purpose of the Assisi meeting was really to say to the religions: "If you think this is important then tell us what you think but don't try and get it agreed with everybody else". The result is that the religions now communicate with each other on the subject of what they are doing for the conservation of nature, not about their religious dogma.

And what happened afterwards? The interesting thing is that after the Assisi meeting there was a press conference and inevitably somebody said: "what are you going to do next?" We said we didn't know… so we [religious leaders and conservationists] sat down afterwards and talked about it. And what we all said was that main thing is that we don't want to burden the whole thing with a new body and its inevitable administration.

I was very reluctant to see another "formal" organisation set up, so I suggested that they should form an informal alliance. At first it was just called a "network", [until 1995, when ARC was established as a fully-fledged charity] the idea being that the WWF would simply act as co-ordinator and technical consultant, to be called on if any of the religions wanted advice.

And they did. One of the people was the Patriarch of Moscow just at the time when the new government of Russia was handing back a lot of the church lands to the Orthodox Church. They were in a sense confronted with this: so we asked WWF for some advice. And it was suggested that some of it could go back to agriculture but others could make very good nature reserves. And then in India the Hindus said: "we've got all these pilgrimage sites, how can we improve them?" And WWF gave them advice. It was the same with the Buddhists in Thailand - who set about trying to protect their forests from poaching and from people poaching trees. And they all ran with it after that.

The idea was that each religion should go off and do its best to "preach the gospel" of conservation and, if possible, to initiate some practical conservation projects of their own.

Have you been disappointed in any of the responses? There are certain inhibitions… the Orthodox Christians have taken it up with a will. But the Western Christians seem to have terrible anxieties about associating the "sacred" with the natural environment. I think there's a sort of folk memory that their predecessors the heathens were worshippers of brooks and trees and stones and streams - so there's a fear that if we show any interest in nature then it implies we're becoming heathens. I think that's the reason, but either way the response has not yet been very good amongst the Western Christians.

Have you been influenced personally by the religious people you have met through your involvement with WWF or ARC? I've often discussed the various philosophies with people of other religions. It's an interesting discussion.

People seem to get awfully dissatisfied with what they've got: they rush off and become something else, some other religion. Which is splendid. But I was born and brought up a Christian and I didn't see a point in looking for anything else. There was plenty there if you wanted to look for it.

You were president of WWF and later WWF-International. Which places did this work take you to, where you witnessed the urgency of conservation?

Many places. The forests of Malaysia and their exploitation; the deserts and erosion in Central West Africa; over-fishing in many fisheries; what were then the polluted lakes and rivers in this country and Scandinavia.

What were some of the administrative problems that you saw there? The curious difficulty when I became president of WWF was that the increase in public donations was going up and we couldn't spend it as fast as it was coming in.

Isn't that a good thing? No not really. You can't just say: "we'll save the rhinoceros" and then do it. You have to do quite a lot of homework to get the project underway. We did the homework and then committed to quite a few projects - and found that the donations started easing off. All charities have this problem. As a charity you aren't really selling something, you are simply saying "give us some money and we will do something good with it". And it usually happens that either your income is outrunning your projects or your projects are outrunning your income. It's quite an exciting business.

You are 82 this year. Looking back over the time that you have been interested in conservation what are the biggest changes you've seen? The world population 60 years ago was just over 2 billion and it's now more than 6 billion. This huge increase - an explosion really - has probably done more harm to the environment than anything else. We take up a lot of room; we use a lot of resources, we harvest and don't replant; we exploit wild fish; we exploit wild forests.

Another big change is how we protect the environment. The National Parks in America for instance are now looked at as protecting the natural environment, but when they were started in the 1930s they weren't that at all. They were parks for people. Now what we're looking at are protected areas for resident species - which is slightly different. It's a positive change that they're there but it's a negative change that they are needed at all.

Do you see any solution? When you start talking about the human population some people think that you want to control it. I don't want to control it: I want people to control it themselves for their own good reasons. Those reasons may be put to them by their religions, by their scientific understanding or simply because of their intelligence. But we are not going to be able to survive on this limited planet if the population keeps on growing: there isn't going to be anything left.

I'm optimistic that the rate of growth of the human population is levelling off. But of course going through to a stable and possibly declining population causes huge economic problems as you can imagine. It means that you get a generally aging population, which economists get in a terrible state about. They don't realise that if you live for longer then you're also capable of doing things for longer.

Some people would like to retire at 60 but a lot of people are perfectly capable of going on and doing things. For example if you're a labourer working very physically on the railways you'll probably have to retire at 50 because you're worn out. But I can drive a bulldozer even now at 82 - and do six times as much work as a gang of labourers could do in the past. The same thing applies in clerical work - when they had to write everything in longhand clerks' eyesight would go very quickly. But now you have machines and clerks can go on indefinitely, or at least as far as I know.

Are the Royal estates run on conservation principles? There is sensible management at Sandringham [in East Anglia] and Balmoral [in Scotland]. It's not anything new.

Sandringham is an agricultural area and everything was going reasonably well at the beginning of the 20th century. There was no cause for anxiety until the post war period. Then agricultural chemicals were used. The first ones were arsenical, which were highly toxic… then they used organochlorine in pesticides and insecticides -which was also highly toxic.

There are different issues in Scotland where nothing has changed much in the past century except acid rain - on moorland and rivers. The variation of biological diversity has changed too. There were too many deer, which damaged the habitat - then there wasn't enough for them eat… And there's another problem - there are not enough salmon any more. There are hundreds of thousands of seals in Britain, which are all protected - they kill more salmon than the fishing fleet. Something needs to be done or you get an imbalance. You can't be romantic or sentimental about conservation, although some things are obviously cruel. A lot of traps were wrong: you shouldn't have to use traps that were cruel.

Do you see yourself as a pessimist or an optimist about conservation? A lot of good things are happening in some parts of the world. In Continental Europe and in this country on the whole there's lots of good news about. But there's bad news too: of course anywhere there's civil war or civil unrest or lack of civil control it's always the natural environment that gets it in the neck. There's also a lot of bad news about fishing. Because it's so difficult to control fishing it's almost impossible to ensure that there will be a continuation of this wild resource. Some people think that fishing is like farming, but it isn't. It's taking things out of the wild.

You have been involved from the beginning: how would you like to see ARC improving over the years? The thing with ARC is that it doesn't exist. There is no "it". There are plenty of members or associates doing their own thing - talking to each other and ARC provides the way of doing that - but they actually do things individually. So if they want to keep talking and be associated with it then that's splendid.

ARC is a means to an end and not an end in itself. It exists to help the religions to make their contributions to the conservation of nature according to their beliefs and traditions. It has no purpose other than to provide technical advice to whatever religion asks for it, about the conservation of nature - and to initiate multi-religious meetings to enable the religions to compare notes and report to each other about their practical conservation projects…

ARC will only be working properly if most people haven't heard of it.

INTERVIEW © ARC. Not to be reproduced in any form without written permission. This interview took place in July 2003.

Words from Prince Philip marking the launch of Sacred Britain, the book of the Sacred Land project

For background about Prince Philip, go to the Buckingham Palace website

Biography:Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, was born Prince of Greece and Denmark in Corfu on 10 June 1921; the only son of Prince Andrew of Greece.

His engagement to Princess Elizabeth was announced in July 1947 and the marriage took place in Westminster Abbey on 20 November. The Queen and Prince Philip had two children before The Queen succeeded to the throne in 1953 - and two children afterwards.

He is Patron or President of some 800 organisations, and has played a prominent part in many aspects of national life. His special interests are in scientific and technological research and development, the encouragement of sport, the welfare of young people, and conservation and the environment.

There is hardly an aspect of the UK's industrial life with which Prince Philip is not familiar. He has visited research stations and laboratories, coalmines and factories, engineering works and industrial plants - all with the aim of understanding, and contributing to the improvement of, British industrial life. As Patron of the Industrial Society, he has sponsored six conferences on the Human Problems of Industrial Communities within the Commonwealth.

Prince Philip was the first President of the World Wildlife Fund - UK (WWF) from its formation in 1961 to 1982, and International President of WWF (later the World Wide Fund for Nature) from 1981 to 1996. He is now President Emeritus of WWF International.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|