Theology of Land

|

|

|

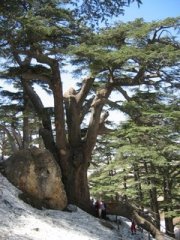

Cedar of Lebanon growing in the Maronite

Protected Environment of Qadisha Valley,

Lebanon.

|

Summary

World-wide the term ‘Sacred

Land’ is being used by environmentalists, religious

communities and heritage organisations. The vagueness of

the term presents both opportunities and problems and

this programme is designed to address, from the

religious perspective, what this term has meant, does

mean and could mean within an overall theological

framework. It also brings into the mainstream of the

debate the major faiths, which for ideological reasons

rooted in Western secular perceptions, have been either

sidelined or ignored in this growing debate. Through the

programme we hope to develop a shared platform of

concern and action helping to better protect the vast

swathes of the world which the major faiths each view as

sacred. To do this, we are inviting the major faiths to

articulate their own Theology of Land.

1.0 A Growth Area of Interest

The rise of interest and of commitment to

ecological issues by the major faiths has been one of

the most significant movements of the past 20 years.

Worldwide, faiths have responded to the climate change

and environment debates in a variety of ways -from

simple auditing of their use of energy, to land reform,

to enhance the protection of nature in their forests and

on their landholdings.

At the academic

level, religion and ecology now features on the syllabus

of many universities and colleges, as well as of

increasing numbers of faith and secular schools.

At

the same time another growth area has emerged – almost

independently of the faith-based movements. This is the

interest in the ecological significance of sacred land.

Anthropologists, ecologists, economists, sociologists

and even psychologists have found much to fascinate them

in the role sacred lands have played in helping preserve

nature.

2.0 Sacred Land and Religious-owned Land

2.1 Sacred Land

From vast

sacred mountains to tiny cemeteries in urban settings,

the faiths have often provided sanctuaries for wildlife.

Up until recently this has tended to have happened more

by accident than by intent, in that simply because a

temple, church, hermit cave or shrine has been situated

on a mountain, in a forest or beside a river, its

presence has created a penumbra of holiness protecting

the land and species around it, sometimes for a radius

of ten miles or more.

We estimate that some

15 percent of the land world wide has a sacred

connotation, from the sacred river valleys of India,

through the sacred mountains of Mongolia to the holy

cities of the Middle East. Although much of this land is

not actually owned by the faith, proximity to a faith

site has led to the area being considered sacred,

regardless of actual ownership.

2.2 Religious-owned Land

On top of this, world wide, the major

faiths do own considerable tracts of land – land which

is not always considered especially holy in itself, but

which has been donated to the faiths to help fund their

vast array of social networks and projects, and which

they often rent out to tenant farmers. We estimate some

eight percent of the habitable land surface of the

planet is owned by religions – ranging from for example

the 10 percent of England owned by the Church of

England, through the 49 percent of Lebanon owned by the

Maronite Church and the 18 percent owned by the Druze -

to the 28 percent of Cambodia seized under the Communist

rule of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970’s and due soon to be

returned to the Buddhists.

3.0 Action So Far

3.1 On Land with a sacred connotation

Some faiths have, in recent years, made

their traditional passive protecting role of land into

an active one.

For example:

*

Buddhist monks in Thailand have built small temples in

threatened forest areas, thus deliberately offering a

degree of protection from hunting and logging.

* Christians in the USA have created

wilderness experiences for young people based on their

Biblical understanding of nature and creation and with a

deliberate intention of encouraging the next generation

to look after the land, because they love the land, and

because they have explored it in the context of being

God’s Creation.

3.2 On Religious-owned land with a commercial

significance

Considerable work to address key uses of

this land has been undertaken by the faiths over the

past few years, aided by ARC in partnership with

organisations such as WWF, the UN and the World Bank

Attention has focused primarily on religiously owned

farmland and forestry. For example:

* Organic

farming training centres run by religious communities

have been created in a number of countries.

* A partnership of the Church of Sweden and

the Shinto of Japan, aided by ARC, has encouraged and

facilitated religious forestry owners to work on their

own forestry standards.

4.0 Partnerships with the faiths – why theologies of

land?

4.1 To remember the element that makes sacred places

special: and give foresters and farming advisors from

the faiths and secular environmentalists a relevant

underpinning to back their practical work

A key element that has been missing from

both the general discussions about sacred land, and from

the practical work on commercially significant land

owned by the faiths has been serious theological

reflection which has been made available to the wider

world. This has meant that the (secular) discussions

about sacred land have often not considered

how the faiths themselves view it. This means not

only that the very element which makes such places

special is missing, but that even the foresters and

farming advisors within the faiths have no theological

underpinning with which to back their practical work.

It is interesting to note that the first

recommendation to emerge from the first meeting of the

faith forestry owners in Sweden in August 2008, was that

each faith should develop a theology of land generally

and of forests specifically - which would then guide how

they develop “faith-consistent forestry management

systems”.

At that meeting it was discovered

that the different theological perceptions of different

faiths produced widely divergent approaches to

understanding and thus caring for or managing the

forests. All of the faiths’ beliefs led them to the

desire to be more thoughtful in how land was used, but

the reasons for this were very diverse.

For

example:

* Both Christian and Islamic

traditions have notions of humanity having a stewardship

role: they can therefore speak about a faith

‘protecting’ a forest or sacred landscape.

*

In Shintoism and Hinduism, this makes less sense.

Shintos and Hindus see us as being protected by the

forest, and from this understanding of the human

situation flows their moral and spiritual responsibility

to care for and with the land.

4.2 To help the next generation understand

A major problem for the continuity of

sacred sites is the loss of the tradition or the

rationalisation of it into purely ecological, economic

or cultural issues. Without the maintenance of the oral

and written traditions, rituals, pilgrimages, rites and

worship at such sites, it only requires a couple of

generations and then it is lost. Developing a theology

of land will help to anchor these traditions into the

mainstream thinking, preaching and worship of the faiths

and thus help to sustain the tradition. Such a

theological exploration can also aid faiths in

rediscovering the significance of stories, actions and

beliefs which have often been relegated to the back

cupboard under the critical eye of modernisers and in

response to criticism from secular bodies.

For

example, it was only when asked about a theology of land

that the Zoroastrians in India remembered that the very

underpinning of their faith was as a response to

environmental crisis and that this was captured in one

of their core theological stories about the earth and

God.

4.3 To underline the importance of protecting sites

sacred to other traditions

In many parts of the world major faiths

share their sacred sites. For example Jerusalem is

revered by Jews, Christians and Muslims while Ayodhya in

India, is revered by both Hindus and Muslims. Added to

this is the fact that a persistent criticism of the

major faiths is that they have sought to destroy sites

sacred to other (particularly indigenous) traditions.

While much of this is hearsay, there are enough examples

of religious extremists attacking sacred trees, groves

and shrines throughout history to warrant concern.

No-one has ever asked the faiths explicitly

to explore their teachings and traditions of respect and

protection of other people’s sacred sites (and sense of

the sacred). Yet all traditions have such teachings and

some faiths have worked on theologies of land. And even

though in many cases a latent ‘let it be’ attitude has

been developed over centuries of co-existence, this can

be disturbed by the rise of more extreme strains of the

major faith tradition. Better to have it explicit.

4.4 Moving on from general theologies of the

environment

The development of these theologies of land

is an important new step, moving us all on from the

general statements and theologies of nature/the

environment which have been produced since the Assisi

Declarations of 1986. These multitudinous statements are

now commonplace and the basic theologies of the

environment for all major faiths have been set forth.

The task of the Theology of Land is to take these

general theological principles and apply them to a

specific issue – land and our understanding and

relationship with it in the framework of faith. While

some faiths have done some work on this, not all have

and none have done so in the context of the wider

discussion and interest in sacred land as a term of

environmental protection and care.

5.0 Ideas on Developing a Theology of the Land

5.1 How?

Each faith has

its own theological structures but certain elements are

held in common. Certain levels of authority exist which

carry responsibility for theological reflection either

because of an academic basis or a traditional role of

decision making. Each faith has touchstones of Scripture

and Tradition from which inspiration and guidance is

drawn or sought.

Most faiths have forums

through which ideas are debated or shared such as

Synods, Councils, Assemblies or media networks.

Finally, most faiths have key individuals or

centres which undertake the task of thinking a little

beyond the normal in order to help the majority of the

faith explore new ideas and fields.

But what

is usually needed is someone or some group who will

start the ball rolling, in full awareness of the role

and significance of elements outlined above.

ARC would therefore like to propose that

each tradition establishes a working group to produce a

first draft of a Theology of the Land from its own

teachings. In doing so they will be joining a number of

other such theological groups around the world - and we

will ensure that at appropriate opportunities

information, insights and problems will be shared

between the groups. However the main purpose of each

group is to address the specific theological insights of

its own tradition.

5.2 What?

So far, from our initial discussions with

several of the faiths, the following key themes and

issues have emerged as an initial indication of the way

we hope each faith will tackle the Theology of Land.

5.2.1 Creation – Existence

a. Who or what created this physical

world?

b. Why does the physical earth exist within

the teachings, stories and traditions of your faith?

c.

What is the relationship between the physical earth and

the rest of nature/creation?

d. Where does humanity

fit into this picture and what role, if any, does

humanity specifically have?

e. Does your tradition

ascribe sacredness to all aspects of creation, including

the land or to specific areas or places only?

5.2.2 Humanity and the Land

a. Within the holy books, is there a

specific theology or series of stories which explain or

set out humanity’s relationship to the earth and to

land?

b. What are the key theological terms used to

describe humanity’s relationship with the land – for

example: steward; protector; protected by; master;

carer; priest; blessing; other

c. What legends,

stories or historical accounts does your tradition have,

which illuminate the way we should relate to, use or

interact with the land?

5.2.3 The Land as Sacred

a. What is your theological understanding

of the role and significance of specific sties being set

aside as sacred?

b. Are there any traditional

practices which embody the faith’s understanding of land

- for example:

* setting aside land for wilderness

habitat for species;

* resting agricultural land on

a regular basis

* the role of natural landscapes as

places of retreat or meditation;

* viewing certain

natural features – mountains, rivers, specific rock

formations etc – as especially charged with spiritual

power or significance;

* traditional practices

which ensure sharing natural resources such as water

with other creatures;

* pilgrimage or annual

rituals associated with the land;

* harvest

festivals or their equivalent such as blessing the land

at spring time

c. Is there a theology of urban

spaces and built communities which differs from the

theology of natural landscapes or agricultural/rural

landscapes?

5.2.4 Spreading the ideas

a. What is the best way of communicating

the theology of land as widely as possible within your

network?

b. Are there current land related issues

for which this could provide a theological framework or

which could be used as tests for the relevance of the

theology to practical issues today?

c. Could you

convene a meeting of those responsible for land

management within your tradition to discuss the

implications of this theology?

6.0 Next Steps

Through these questions and the debates

which we hope they will initiate, plus the other

questions or issues that each faith will identify as

particularly important, we aim to help the faiths

discover or explore perhaps for the first time, a

fundamental aspect of their theologies of ecology –

namely what is the earth and what is our relationship to

it?

7.0 An Invitation

We

invite you to create a working group which will produce

by April 2009 an initial outline document reflecting

upon the issues of a Theology of Land for your

tradition. Once you have completed this please send it

to us at ARC and we will respond with ideas and

suggestions. Following a meeting, which we hope to hold

in the summer of 2009, we would ask you to finalise the

discussion document for your Theology of Land and to

then discuss with us how this can be brought into wider

discussion within the decision making structures of your

tradition.

Our hope is that by 2012, all key

religious traditions will have in place such a

theological document on the subject of land, designed to

stimulate debate, reflection and action.

ARC

Links

Link

here

for more details of ARC/UN 7 Year Plan and the Use of

Assets.

|