| |

|

|

Making Buddhist teachings on protecting nature more relevant

April 25, 2012:

|

|

|

Mongolian Buddhists launched a long-term eco-plan in 2009 |

In April 2012 over 1000 Buddhist monks, nuns and scholars from 50 countries gathered in Hong Kong for the third World Buddhist Forum.

ARC Secretary General Martin Palmer presented a paper on the challenges and opportunities facing Buddhism in the current globalised world situation. The full text is given below, or you can download a PDF copy here.

The development and mission of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism in the era of globalisation.

Martin Palmer Secretary General, Alliance of Religions and Conservation

Buddhism has the honour of being the world’s first openly missionary religion. Spreading out from its homeland of Northern India, it famously sent missionaries to not just Asia but even to Greece during the reign of the great Buddhist King Ashoka in the 3rd century BC. It is perhaps to the Edicts of Ashoka that we should turn for inspiration and guidance as to the heart of the message Buddhism should have for the global world society today.

|

|

|

Martin Palmer and EMF's Allerd Sticker at a meeting with Shanghai Buddhists about urban nature protection |

On the famous stone pillars he erected throughout his kingdom he inscribed the teachings and resulting virtues and actions which he felt arose from following the Dharma. For example:

All men are my children. What I desire for my own children, and I desire their welfare and happiness both in this world and the next, that I desire for all men. You do not understand to what extent I desire this, and if some of you do understand, you do not understand the full extent of my desire.

You must attend to this matter. While being completely law-abiding, some people are imprisoned, treated harshly and even killed without cause so that many people suffer. Therefore your aim should be to act with impartiality. It is because of these things — envy, anger, cruelty, hate, indifference, laziness or tiredness — that such a thing does not happen. Therefore your aim should be: “May these things not be in me.” And the root of this is non-anger and patience. Those who are bored with the administration of justice will not be promoted; (those who are not) will move upwards and be promoted. Whoever among you understands this should say to his colleagues: “See that you do your duty properly. Such and such are Beloved-of-the-Gods’ instructions.” Great fruit will result from doing your duty, while failing in it will result in gaining neither heaven nor the king’s pleasure.

|

|

|

Bhutan Buddhists are planning long term environment protection |

He saw Buddhist compassion as being not just for humanity but for all life:

Twenty-six years after my coronation various animals were declared to be protected — parrots, ruddy geese, wild ducks, bats, queen ants, terrapins, boneless fish, fish, tortoises, porcupines, squirrels, deer, bulls, wild asses, wild pigeons, domestic pigeons and all four-footed creatures that are neither useful nor edible. Those nanny goats, ewes and sows which are with young or giving milk to their young are protected, and so are young ones less than six months old. Cocks are not to be caponized, husks hiding living beings are not to be burnt and forests are not to be burnt either without reason or to kill creatures.

One animal is not to be fed to another..[at special festivals]…, fish are protected and not to be sold. During these days animals are not to be killed in the elephant reserves or the fish reserves either...[on special times of the year]…bulls are not to be castrated, billy goats, rams, boars and other animals that are usually castrated are not to be. horses and bullocks are not be branded. In the 26 years since my coronation prisoners have been given amnesty on 25 occasions.

The same problems 2,300 years onIn a world where meat eating, destruction of species for Traditional Chinese Medicine or for their skins, tusks or other parts, deforestation and cruelty towards other humans have all become so prevalent, we would do well to remember that over 2,300 years ago Ashoka saw these same problems. His response was to relate his new Buddhist faith to solving these issues. His response was to issue decrees.

|

|

|

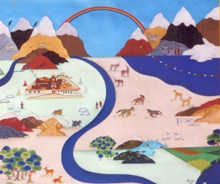

Contemporary Buddhist mandala about protecting nature |

It is not so easy for Buddhists today to do this. Instead we perhaps need to fuse the Theravada wisdom of Ashoka and the Theravada tradition of Teaching (hence their title) to the Bodhisattva compassion and wisdom embedded in, for example, the Lotus Sutra. You will all know of course, of the vision of the Compassionate Bodhisattva Kuan Yin who decided to use her immeasurable store of merit to help all sentient beings struggling to escape the consequences of their karma. It is magnificently expressed in this section from the Lotus Sutra:

Every evil state of existence,

Hells and ghosts and animals

Sorrows of birth, age, disease, death

All will thus be ended for him.

True regard, serene regard,

Far-reaching, wise regard,

Regard of pity, regard compassionate,

Ever longed for, ever looked for

In radiance ever pure and serene!

Wisdom’s sun, destroying darkness,

Subduer of woes, of storms, of fire,

Illuminator of the world!

Law of pity, thunder quivering,

Compassion wonderous as a great cloud,

Pouring spiritual rain like nectar,

Quenching all the flames of distress!

Sometimes we in the faiths strive too hard to make our teachings and traditions “relevant” to the modern world. In the case of Buddhism and its core missions I don’t think this is necessary. The core teachings of Buddhism about illusion, about the nature of reality and the nature of compassion are eternal. They are truths we need to hear today as much as in the time of the historical Buddha, Ashoka, Bodhidharma or the Sixth Patriarch.

So the question is not: “What is the mission of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism?” but: "How it might be undertaken?".

How did the Buddha's teachings survive for so long?The Buddha achieved two remarkable new developments in religious activity during his long life. First of all he made profound and complex doctrines easily graspable by producing simple yet deep teachings in the form of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. Later Buddhism refined this further into the Three Noble Truths. Wisdom was thus made accessible to the ordinary people through such simple to learn and understand methods. He was the first popularist – someone who could encapsulate an entirely new way of seeing, thinking, being and believing in a few lines. This is why his Dharma has survived while the thousands of other Teachers who were around at the same time as him have not.

So one lesson is to be simple, clear and helpful. To tell stories rather than pontificate; to explain rather than confuse. To use just a few words and some powerful images rather than write vast books which most people either cannot or will not read.

The second remarkable new development was to give his Dharma a living witness in the form of the Sangha. There were thousands of teachers at this time, each with many disciples, but with the exception of Mahavira and the Jains no other teacher established living witnesses to the Dharma. No one else set up a Community set apart to witness to the impact the teachings can have on a person’s life. No one else showed what a life lived in accordance to the Dharma might actually look like.

The Buddha also did not make the crucial usual mistake of teachers. He did not elevate himself to such an extent that when he died, the charisma and energy of his movement died with him. He avoided this through the two innovations listed above and also by ensuring that he enabled everyone to find their own path, not just become followers of his path.

Theravada Buddhism has preserved this sense of the individual path and it is a vitally important contribution to reaching out to a confused world. Charismatic figures burn out and they often destroy more than they save or redeem.

So Buddhism needs to look at the ways in which simple messages can be shared – and for this the world of social media is a wonderful new tool, almost ideally suited to the notion of rendering great teachings into catchy, easily shared sets of four or eight or three simple ideas.

Buddhism also loves to tell stories. I have translated some of the wonderful stories of Kuan Yin and these teach far more than, for example, the Hua Yen Sutra because the stories speak to us and our lives directly while the Hua Yen demands years of study and great knowledge and thus is a closed book for most people.

Again, the contemporary world loves stories. Film, plays, novels, poetry – they all use and tell stories and we should share the great Buddhist stories with them. Think of the impact of the tales of the Monkey King, with their fabulous collection of events from the arrogance of the Monkey King through his adventures with Tripitaka and the others and through to his final enlightenment. More people probably have an understanding of the Buddhist pathway through life from the Monkey King stories than from any other source. Buddhists should use this to further people’s awakening to the deep truths and lifestyles of Buddhism.

And lifestyles are crucial as well, which is why the Buddha founded the Sangha. The vegetarian lifestyle of so many Buddhists; the simplicity; the sense of being part of a bigger community – these are all insights and ways of living which our world is hungry for. We should have more monks and nuns walking into our cities – not just in the East but in London, New York, Rome, Rio – asking those who pass by to look again at the values they live by in comparison to those of the monk with his alms bowl.

Buddhism understands globalisation. It was the first faith to go global as a conscious decision. When Ashoka sent out those missionaries in pairs to bring the teachings to peoples thousands of miles from the north of India, he and the Buddhist community understood that as the world became more and more intertwined it needed to be linked not just by economics, nor by empires or trade, nor even by shared languages. It needed to be linked by a shared understanding of reality and a shared sense of compassion. So globalisation is nothing new for a faith which started in Northern India and expressed in Sanskrit and Pali before spreading into languages as diverse as Chinese, Tibetan and Japanese and is now available in hundreds of languages.

What does need to happen is that we must not be afraid to use the powerful international languages of today to convey the Buddhist message. Sanskrit was chosen because it was the English of its day – used across continents and through kingdoms and cultures. Today we have similarly powerful languages and we need to use them, to live inside them rather than try to make people become Tibetan speakers or Sanskrit readers.

Likewise we need to remember that the images of the Buddha, of the Bodhisattvas and deities are culturally formed and not always helpful. My good friend Stephen Batchelor has written of how alien and unhelpful many of the Tibetan depictions of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are and how we need to move beyond them to create images which make sense to a non-Buddhist world. This requires courage to explore and experiment and to look at each of the great cultures of our world and ask what images mean most to them.

We need, in other words, to not lock up Buddhism in antiquated images and language which was once radical, revolutionary and culture defining but now is old fashioned and, frankly, so culturally specific it becomes an obstacle. Let’s remember the Buddha’s warning: only a fool looks at the finger that is pointing to the moon. Are we in danger sometimes of elevating a particular form of cultural Buddhism to the statues of the teachings and wisdom itself? Remember how in the Lotus Sutra the Buddha says that to save a sentient being he can appear in whatever form will help that person – as a Brahmin, as a tree, as an animal or a fish – whatever form will help that person to understand the truth.

Too much of contemporary Buddhism can appear to be a romantic escape to a pretend world of living in ancient Tibet or ancient China when what we need is for this eternally wise teaching to enter into the world of cars and money, trade and TV, advertising and Facebook and to speak to us as we speak there (and not in some romantic old fashioned way).

This requires missionaries from Buddhism to have the courage to go into cultures expecting to find the Buddha already there and to then help those there to recognise him and his wisdom in the midst of their own culture. It requires missionaries to do this and then to turn that world upside down from within in exactly the way that the Buddha did to the conventional Vedic wisdom of his age by changing the understanding of soul. This was also the transformative way Ashoka changed what it meant to be a great ruler and the way Bodhidharma did to the Emperor when he refused to speak for ten years and instead literally turned his back on the world of power.

The mission of Buddhism is therefore to be bold and to find the simplest ways to express its teachings. To tell stories, both the great old stories and also new stories which tell the same truth. It needs to realise that Sanskrit words or Tibetan deities are not the unchangeable truth and that while they have been useful in certain contexts they are not universal. The truth is universal but the format will always be limited by culture, language and history.

Buddhism is greater than that and rediscovering that is perhaps the greatest contribution to globalisation. Because, what it does is explain that the Buddha could have come as an Englishman, an Arab, an American, or a Russian if it meant that he could reach people and that he could have spoken their languages and used their artists to express the wisdom he came to share.

To do this Buddhists also need to look at what they can do as Buddhist communities to show these teachings, this wisdom to the world because too often Buddhism remains a great idea that no-one seems to be really practicing.

First of all Buddhists can help communities to strip away illusion. The illusion that we can exploit this fragile world and not pay the cost of such abuse; the illusion that material property is the only worthwhile goal; the illusion that human communities can exist without regard to the other communities of animals, plants, rocks, rivers and mountains. Buddhism can restore a holistic vision of our place in the world and our responsibilities.

Secondly, Buddhists can set an example in protecting species. For example, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is a vital part of Chinese spiritual and medical heritage. It plays a significant role in health care in China and has also become very popular around the world. Some unscrupulous people use endangered species such as tigers or rhinos to make such medicine but in doing so they are destroying part of nature.

Buddhists can point out that a medicine designed to harmonise the vital forces in the body, but which itself destroys the harmonious balance of nature, cannot be good medicine and will bring Karmic retribution instead.

Buddhists can therefore encourage responsible use of resources for Traditional Chinese Medicine. They can join the many other faiths around the world who are working to stop this terrible trade and abuse of nature. Show the Bodhisattva compassion by never ever using TCM which uses endangered species and speak out powerfully in your communities against this killing and suffering caused in the name of healing.

Thirdly, Buddhists can look at their own resources and how they use them. Many monasteries own land: is this farmed ecologically - organically? Many monasteries are on sacred mountains: do they help protect the ecology, for example by creating tree nurseries or by clearing rubbish from the hillsides?

All monasteries use paper, energy, transport and foodstuffs: is the paper eco-friendly? Is the energy renewable? Is the transport using as little petrol as possible and are the foodstuffs ethically and environmentally produced - e.g. free of chemical sprays or fertiliser? Is the monastery itself a model of ecology? What is it built from? Is it renewable (e.g. wood or stone)? Is it ecological in its use of gardens and does it have an eco-friendly car park?

Finally, Buddhists are teachers. That is what the Sangha has as a major role. So can we create educational projects? For example, leaflets for pilgrims and visitors to take home, which teach them how to live compassionately in their own community. Or special day courses for groups such as local farmers or local business people, on how to live as good Buddhists for the environment.

When Buddhism is lived it will speak without using words. When it speaks without using words everyone can understand it. If you have to use words, use the words people know, love and understand. The Buddha saw that illusion was at the heart of the world’s problems. Buddhism needs to ensure that it does not become itself an illusion but a witness to the reality of the Buddha’s teachings and life.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What does Buddhism teach about ecology?

A brief outline of the teachings of ecology in Buddhism |

|

The Buddhist Declaration on Nature - Assisi 1986

The original Buddhist Declaration on Nature was created in 1986, at a meeting held in Assisi by WWF-International. It stemmed from an idea by HRH the Prince Philip, at which five leaders of the five major world religions – Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism – were invited to come and discuss how their faiths could help save the natural world. |

|

April 25, 2012:

Making Buddhist teachings on protecting nature more relevant

"Sometimes we in the faiths strive too hard to make our teachings and traditions relevant to the modern world. In the case of Buddhism I don't think this is necessary. The core teachings of Buddhism about illusion, reality and the nature of compassion are eternal. They are truths we need to hear today as much as in the time of the historical Buddha" - Martin Palmer at the 3rd World Buddhist Forum, Hong Kong |

|

|

|

|